At the edge of the Ecuadorian Amazon sits the little-visited Parque Nacional Sumaco Napo-Galeras. Just six hours from Quito by bus, the park covers a wide variety of elevations ranging from 500 meters (1640 feet) above sea level to the summit of Sumaco Volcano at 3,830 meters (12,566 feet). Along with the large range of elevations, there are a variety of different kinds of soils, thanks to the numerous volcanic eruptions that have occurred throughout the region’s history. This huge variety in elevation and soils creates a huge variety of environments, which in turn makes the area extremely biodiverse and ecologically valuable.

How diverse and how valuable?

No one really knows! Due to the park’s remoteness, it is little-studied (1). Preliminary studies have found over 6000 species of plants in the park (2), which is more than can be found in the entire state of California (3). One researcher has also suggested it could be one of the best places to see wildlife in Ecuador, due to the abundance of large carnivores like jaguars, pumas, and ocelots (1).

Yet despite the park’s richness, the people who live nearby are some of the poorest in Ecuador. The poverty has forced many people in the area to resort to deforestation to feed themselves and their families. But many locals, with help from both the Ecuadorian and German governments, have been working really hard to develop tourism in the area, with the goal of allowing people to make a living without damaging the forest.

The crown jewel of the tourist program is the trek to the summit of Sumaco Volcano. The trip is 42 kilometers (26 miles) out and back and normally takes three days. The trail goes through dense jungle, cloud forests, and high alpine environments to one of the highest peaks in the Amazon. A guide for the trek is both required and necessary, as there are parts when the trail winds through farmland and there are no signs designating which way to go.

Yet despite the grandeur of the area, bringing in tourists is easier said than done, especially since there is not much information on visiting Sumaco Volcano online. In an effort to get more people to see this amazing place, I am including instructions on how to visit Sumaco. Please let me know if you have any questions!

Points of Contact

- Edwin, host of the lodging in Amarun Packcha (Spanish only): +593-098-373-9145

- Pacto Sumaco (Spanish only): +593-06-301-8324

- Pacto Sumaco Tourism Facebook Page: https://es-la.facebook.com/ctcpactosumacos/

- WildSumaco Lodge, an ecolodge in Pacto Sumaco that I heard has English speakers who can help people who do not speak Spanish organize trips to the summit of Sumaco Volcano: +593-2202-2488, +593-987-792-773, info@wildsumaco.com

Summary

This article is long! If you can’t make it through the whole thing, here is a shortened version.

We took a bus from Quito towards the town of Coca. We got off in the Kichwa community of Guagua Sumaco and spent the night in Amarun Pakcha, the town’s tourist area. The next day, we took a truck down a dirt road to the smaller Kichwa community of Pacto Sumaco, where we started the trek to the top of Sumaco Volcano with our guide. The trek normally takes three days, but due to bad weather, it took us four. On the fourth day, we made it back to Pacto Sumaco, where we took a truck to Guagua Sumaco, then a bus back to Quito.

Getting There

The trail to Sumaco Volcano begins in the small town of Pacto Sumaco. To get there, we started by taking a bus from Quito to the city of Coca. Before reaching Coca, however, we got off at the bus stop for the town of Guagua Sumaco (also called Wawa Sumaco). The bus normally does not stop there, so we had to ask to be let out there. We spent the night in Amarun Pakcha, the ecotourist area of Guagua Sumaco. The next day, we took a truck taxi down a dirt road to Pacto Sumaco, where we headed to the park administrative building to organize our trip.

Map of the route from Quito all the way to the summit of Sumaco Volcano.

What We Did

As I stated earlier, we could not find much information on visiting the Sumaco area before I left. All we had was the phone number for Edwin, the man in charge of tourism in Guagua Sumaco. The day before we left, we called Edwin, reserved a place to stay for one night, and hoped we could figure out everything for the trek to the volcano once we arrived.

Upon getting off the bus, we found some wooden signs directing us down a dirt road to Amarun Pakcha. As we walked down the road, we ran into Edwin, and he showed us the rest of the way to Amarun Pakcha, then gave us a tour of the area.

As we talked to Edwin, it was clear that Spanish was not his first language. He told us this is because both Guagua Sumaco and Pacto Sumaco are Kichwa communities, and that almost everyone there speaks the indigenous language of Kichwa at home. The Kichwa people and language are widespread throughout the Ecuadorian Amazon and, according to one person I met later on, also throw the best parties in the country.

Amarun Pakcha is named after the nearby waterfall, Amarun Pakcha. The name Amarun Pakcha is a Kichwa word, meaning boa falls. The name originated at the community’s founding in 1979, when a group of Kichwa people left their homes to start a new life elsewhere. After walking for 3 days, they came across a waterfall with a boa constrictor sitting on a rock overlooking the falls. They decided to settle there, and named the falls Amarun Pakcha.

Amarun Pakcha.

After visiting the falls, we headed back to our lodging, where a few people from the community cooked dinner for us over a fire. During this time, we told Edwin about our plan to climb Sumaco Volcano and he said he could organize a guide and a ride to Pacto Sumaco for the following day.

Our ride arrived at 9 am the next day. It was a truck that took us down the bumpy dirt road to Pacto Sumaco. In Pacto Sumaco, our driver dropped us off in front of park headquarters, where a man who I assume was the park administrator was waiting. As we filled out some forms, he fitted us with knee-high boots and gave us some background information about the park.

During this time, a number of people from the community began to coalesce to see us off. Trips to the summit are not terribly common, with only about 2 going out per month. In addition, most of the people who climb Sumaco Volcano are Ecuadorian, so seeing two Americans set out to climb the peak was even more unusual. As a result, a lot of people wanted to talk to us.

Once we had finished getting ready, we were introduced to our guide, José, and began the trek. As proof that guided trips to Sumaco Volcano began only recently, José was both 22 years old and the most experienced guide in Pacto Sumaco. I told him that I was also 22 and an outdoor guide in the United States, and we talked about our jobs to see how treks vary between our two countries.

To start, tent camping is not nearly as common here in Ecuador as it is in the United States. People making the trek to Sumaco Volcano, for example, instead stay in wooden lodges, or refugios, built along the route. Staying in lodges, hostels, and homestays is the norm for many treks in this part of the world. While some treks do require hikers to stay in tents, these are less common.

Since most people stay in lodges, there is also less of an emphasis on self-sufficiency. For example, when I worked as a backcountry guide in Montana, we ran 1-2 week trips where we carried everything we needed on our backs. On this trip, however, we only carried clothes, sleeping bags, and some snacks for the day, since the refugios had already been stocked with food, cookware, and everything else we would need. This difference was a huge plus for us, since it allowed us to travel with backpacks so light they would make even the most dedicated ultralight backpackers jealous.

Yet in spite of our light packs, the going was very hard. For the first few kilometers, the trail ran over wooden boards through pasto, or pastures.

Following José through the pasto.

But after those first few kilometers, we passed the sign designating the national park, and the terrain changed considerably. The wooden boards went away, and the trail became very muddy. We had to step carefully, because in some places we could sink up to our knees in mud. For the first time in my life, I was glad to be hiking in boots.

Despite the terrain, José told us we were walking at a good pace. We had left Pacto Sumaco at 10, and by 2 we had reached a long, steep ascent José called La Cuesta de Los Lamentos, or the slope of complaints. The refugio where we would be spending the night laid at the top of the hill, and the slope was the last part of the day’s hike. After much complaining, we made it to the top around 3, where our refugio was waiting.

It took us 5 hours to walk the 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) to the refugio, which José said was the fastest any group had completed that section. This was a testament to just how rough the terrain was, since less than 2 miles/hour is a very slow hiking pace by any standard.

After stopping to catch our breaths, José showed us around the refugio. Despite being deep in one of Ecuador’s most remote national parks, it was quite developed. The refugio had solar electricity, a gas stove, flush toilets, and a spectacular view of both the Amazon and Sumaco Volcano. The only thing it was lacking was hot showers.

Watching the sun set over the Amazon from the refugio.

The summit of Sumaco Volcano peeking out from the clouds.

Shortly after arriving, we cooked and ate dinner. We were all set on going to sleep early, since the plan was to wake up the following morning at 2:30 so we could make it to the summit in the morning and avoid any afternoon thunderstorms.

By 8 pm, we were all in bed. As we fell asleep, rain began to fall.

When we woke up the following day at 2:30, it was still raining, and raining quite hard. José did not want to risk being caught in a storm near the summit, so we waited for the rain to stop. We waited and waited, and eventually went back to sleep. When I woke up again at 8, it was still pouring. We ate and slept off and on all day as we waited for the rain to stop, but it was relentless. By noon, we realized we would not be able to reach the summit that day, so we decided to stay another night and hope for better weather the next day.

Around 6 pm, the rain finally stopped. It picked up again a few hours later, but we woke up at 2:30 the next morning to clear skies. By 3:15, we were on our way.

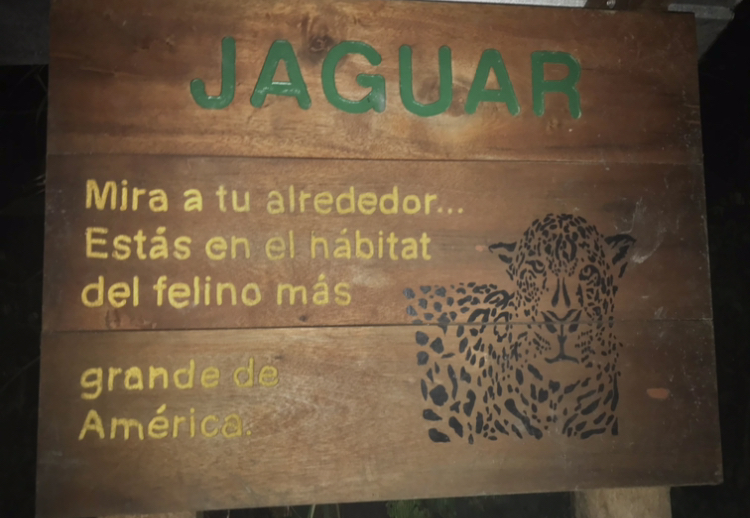

Hiking through the cloud forest in the dark was a truly special experience. The green of the trees, moss, and other plants seemed especially rich in the moonlight, while water from the previous day’s rain dripped off of every branch. Animals we could not see made noises all around us, and in the dark we even came across an unsettling sign warning us of jaguars.

“Look at your surroundings… you are in the habitat of the largest cat in the Americas.”

Around 5:30, we made it to the edge of the forest floor and began the climb up the volcano.

This section was the hardest part of the hike yet. The trail took the most direct route up the volcano, which forced us to make a steep ascent by walking at a nearly constant 45 degree angle. Some parts were even steeper, and these steep sections seemed to be the muddiest of all, causing Gabe and I to slip and fall many times.

Still, we climbed higher and higher through the cloud forest. It seemed the higher we climbed, the greener the forest became. In some areas, we could not see anything except green; the trail, the trees, and even the sky were all blocked out by various mosses and climbing plants. In the cloud forest, no space was left unvegetated.

The cloud forest on the way to the summit of Sumaco Volcano.

Eventually, we were out of the cloud forest altogether and above the trees. Here the climbing became even more difficult, because there was little to grab on to when we fell. But as we climbed, the views became more and more spectacular.

Gabe and José making the steep climb up Sumaco Volcano. The refugio where we slept lies in the hills in the middle ground of the photo.

For one section, we climbed through a thick fog, then when we came out on the other side, we realized we had climbed above the clouds. Shortly after, we reached a false summit, where we stopped to admire the view before making our final push to the real summit.

View from the false summit en route to Sumaco Volcano.

We climbed up into yet another layer of clouds, and at precisely 10 am reached the true summit of Sumaco Volcano. José told us that the summit is always covered in clouds; of the roughly 100 times he has reached the summit, only once was it clear. That day, he said he could see Cotopaxi, Sangay, and most of Ecuador’s major peaks. But we were content to just relax amongst the clouds and have a snack on the summit.

The summit of Sumaco Volcano.

After enjoying the peak for a while, we turned back and headed to the refuge. As we descended, we realized that the beautiful layer of clouds we had climbed above earlier had turned into rain. So as we descended, the trail became muddier and muddier and the weather rainier and rainier.

The going at this point was especially slow. Descending the muddy trail was even more treacherous than ascending, and I personally slipped and fell at least a dozen times. The rain, while not quite as intense as the day before, was nevertheless quite heavy. That day, we did not get back to the refugio until 3:00.

We hiked just 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) that day, but it took us almost 12 hours. The terrain we crossed that day was far more difficult than that of the first day. The hike to the top of Sumaco Volcano was without question one of the most difficult hikes I have ever done, but also one of the most worthwhile. The views, diversity of environments, and overall ruggedness of the trek are unlike anything I have ever done before, and I would happily go back to climb the volcano again.

After some dinner and another night’s sleep, we hiked back to Pacto Sumaco, took another truck to Guagua Sumaco, then hopped on a bus all the way back to Quito.

Sources

- A.-M. Hodge, Sumaco: Ecuador’s Beacon of Biodiversity. Scientific American (2011), (available at https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/sumaco-ecuadors-beacon-of-biodiversity/).

- I. Endara, K. Campoverde, L. Altamirano, J. Onofa, N. Chuquín, G. Aguirre, H. Cifuentes, B. Torres, R. Chapalbay, A. Gómez, X. Izurieta, T. Villegas, “Plan de Manejo del Parque Nacional Sumaco Napo-Galerias” (Ministerio del Ambiente Ecuador, 2013), (available at http://suiadoc.ambiente.gob.ec/documents/10179/242256/42+PLAN+DE+MANEJO+SUMACO.pdf/477bfee3-341c-4efa-86c0-0689734994f0).

- 3. B. A. Stein, K. Gravuer, “Hidden in Plain Sight: The Role of Plants in State Wildlife Action Plans” (NatureServe, 2008), (available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269111706_Hidden_in_Plain_Sight_The_Role_of_Plants_in_State_Wildlife_Action_Plans).